ICZN in Its Own Tangle on Inconsistencies and Contradictions

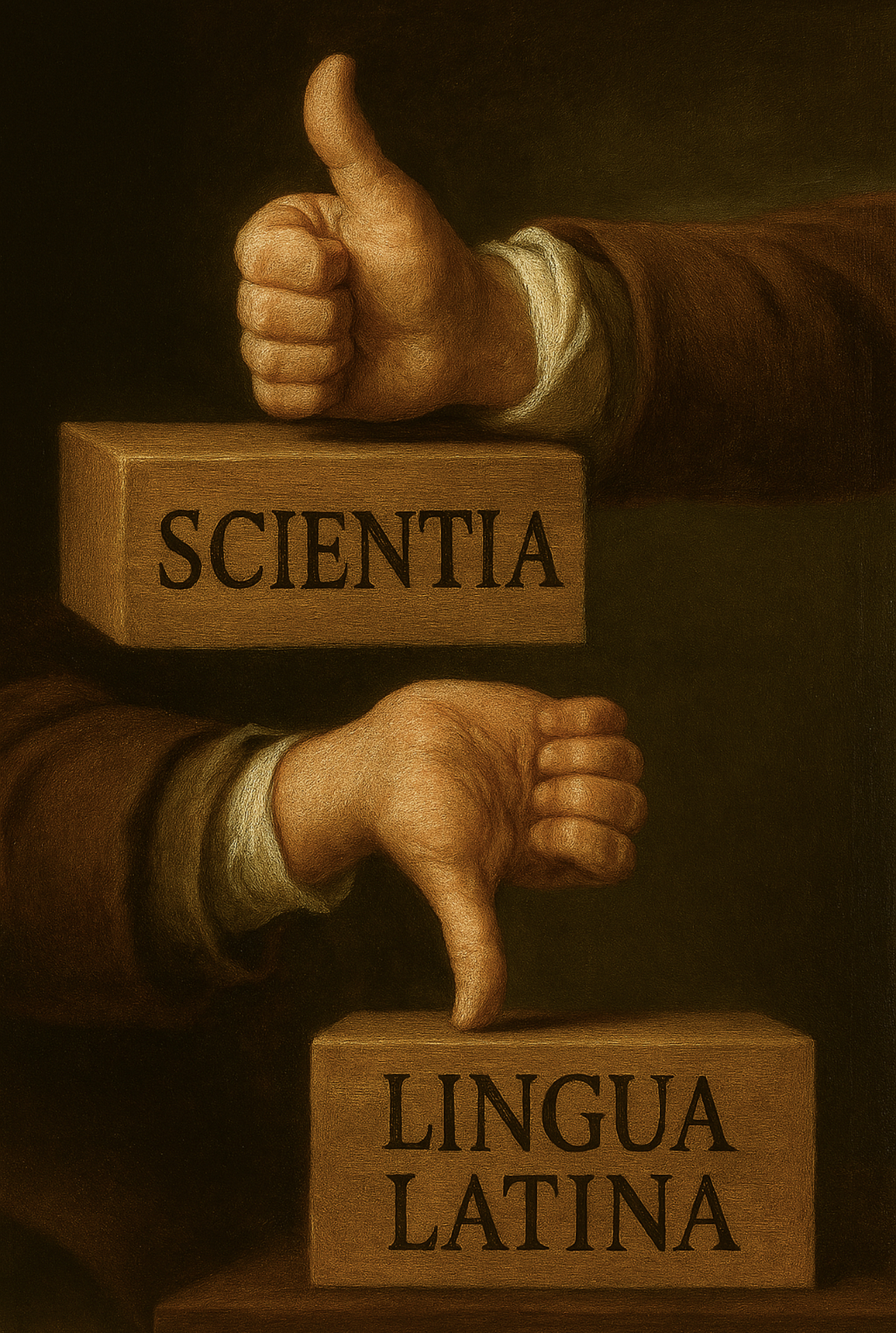

Zoological Science, Yes — Linguistics Degraded

It is not anything new that scholars with classical Greek and Latin education claim that the current practice of the International Commission for Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), in interpreting and regulating the rules of zoological nomenclature, treats the Latin language like a disposable tool — as if it were not a diverse and respectful subject, and as if linguistics were not a science. This is a regrettable tendency, because from the very beginning, taxonomy has been one of the first truly interdisciplinary sciences, founded both on the classification of nature and on the roots, grammar, and semantics of the noble Latin language — the language of educated people, scholars, and philosophers from ancient times until now.

Two areas in particular reveal a great deal of barbarism — that is, questionably technically correct names formulated in a barbarian and uneducated way, not respecting the spirit and, in many cases, not even the grammar of Latin. These are:

1. The naming of species in honor of persons

2. The derivation of names from geographic terms

Classical Naming Traditions

The classical way, always used by old scholars to honor a person and dedicate a new taxon to them, was to Latinize the name of the person or persons and then:

1. Form the genitive case using endings like -i, -ae, -um, -orum, -arum (e.g., boulengeri, einsenmannae, champanorum)

2. Form an adjective by adding the suffix -ianus, -iana, -ianum to a father's name or family name, indicating descent or association (e.g., linneana, davidianus)

ICZN's Contradictions

Now comes the ICZN. In Article 31.1, it states:

"A species-group name formed from a personal name may be either a noun in the genitive case, or a noun in apposition (in the nominative case), or an adjective or participle."

And in Article 31.1.1:

"A species-group name, if a noun in the genitive case formed from a personal name that is Latin, or from a modern personal name that is or has been latinized, is to be formed in accordance with the rules of Latin grammar."

So — where are the inconsistencies?

Three Major Inconsistencies

1. Participles from Personal Names

Latin does not form true participles directly from personal names, because participles are derived from verbs, not nouns. You can use a Latin participle as a species epithet to honor a person only symbolically — by choosing a verb that reflects their contribution or trait, but not by deriving it from their name.

For example:

Person: Linnaeus

Verb: ordinare (to organize)

Participle: ordinatus (organized)

This is not a participle of the person's name, but of a verb metaphorically honoring them. So, ICZN codifies a non-existent option: the patronym in this case is not derived from a name but from something else, just contextually related to it.

2. Nominative Case Misuse

Stating that the name must "be in accordance with the rules of Latin grammar" contradicts the allowance of "a noun in apposition (in the nominative case)," because such a name cannot be formed in Latin in the nominative unless under two rare exceptions:

When the name refers to itself, e.g., Urbs Roma (the City of Rome), Senator Iulius (Senator Julius)

When used mockingly or humorously, e.g., Canis Flavius (the Dog Flavius), which would be considered extremely rude and unacceptable in scholarly naming

Therefore, nouns in apposition in the nominative are barbarian and meaningless. What are we to make of names like Rana boulenger or Triton darwin?

3. Recommendation vs. Permission

ICZN allows nouns in apposition in the nominative, but literally does not recommend it.

Recommendation 31A states:

"An author who establishes a new species-group name based on a personal name should preferably form the name in the genitive case and not as a noun in apposition, in order to avoid the appearance that the species-group name is a citation of the authorship of the generic name."

So — a paradox: you can do it, but you shouldn't. For a good reason. But the reason is already there: it doesn't make sense anyway and it conflicts with Latin grammar.

Geographic Names: Same Mess

The same nonsense appears in geographic naming. The old scholars' practice was:

1. Use the genitive of the name (jubae)

2. Use the suffix -ensis, -ense (indochinensis)

3. Use an adjective derived from the name (arabicus)

But ICZN allows names as nouns in apposition in the nominative here too. How is it acceptable that a snake should be named Tantallia insulamontana, or that a tiny chameleon should bear a specific epithet in plural: Rhampholeon monteslunae?

Conclusion

This is nor wise. It makes no sense. It offends old scholars, Latin, and linguistics. It is time to initiate changes.