Myth 107: “Veiled Chameleons Are Non‑Native in Florida But Not Invasive”

The Claim

Because veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus) are exotic pets, some argue they are simply non‑native residents in Florida, harmless curiosities rather than invasive threats.

The Reality

This is incorrect. By U.S. law and Florida's own wildlife management standards, an invasive species is defined as a non‑native organism whose introduction causes, or is likely to cause, economic, environmental, or human health harm. Veiled chameleons meet this definition:

Non‑native: They originate from Yemen and Saudi Arabia, not Florida.

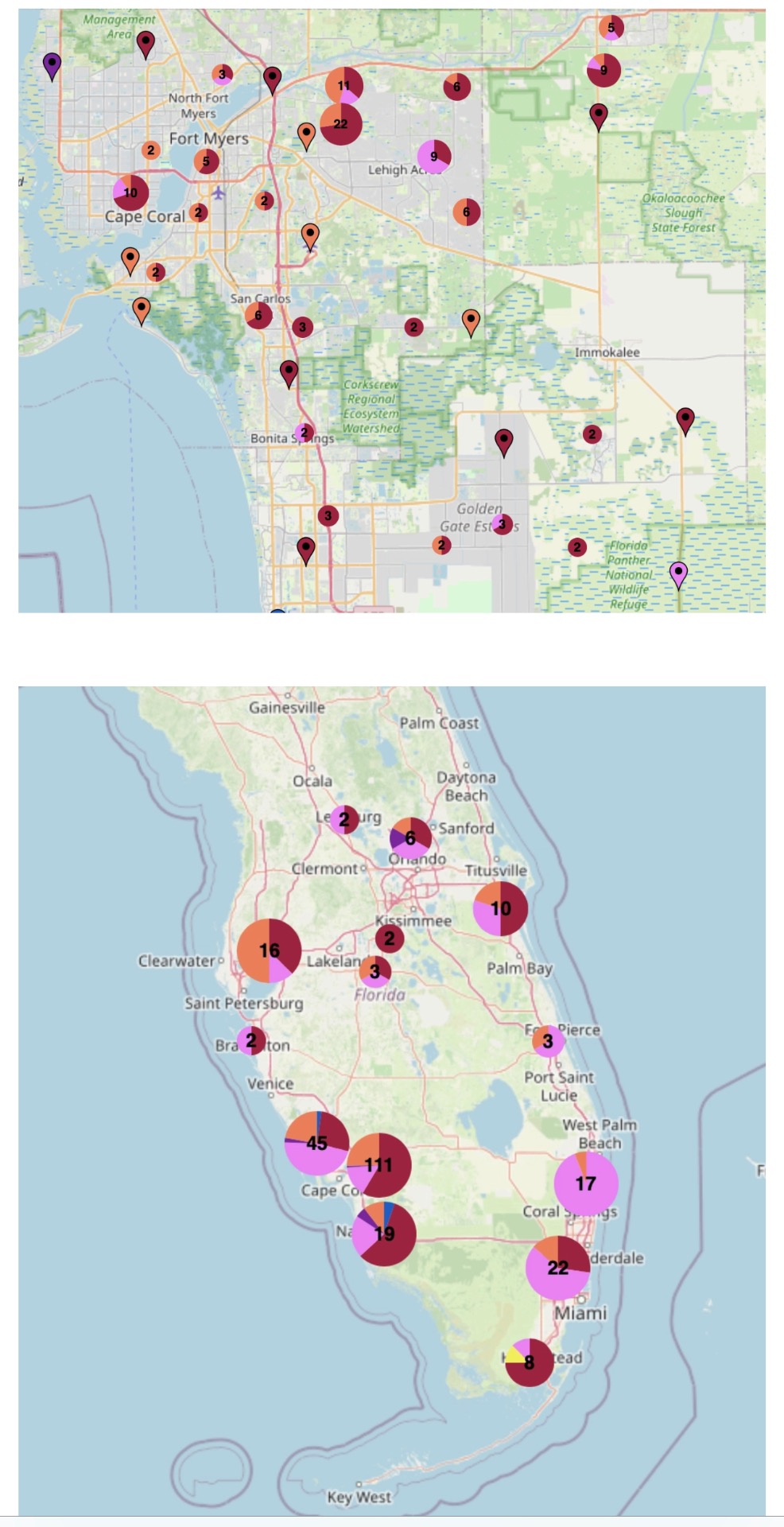

Established: Breeding populations have been documented since 2002, now spread across more than 20 counties.

Ecological impact: They prey on native insects and reptiles, compete with local species, and disrupt ecological balances.

Human factor: Their release is tied to "chameleon ranching" practices—deliberate introductions for later collection—fueling illegal wildlife trade.

Narrative

The myth persists because veiled chameleons are visually striking and popular in the pet trade. Their presence in suburban yards or pine scrublands can seem like a whimsical accident of nature. Yet beneath the fascination lies a forensic reality: these reptiles are not passive guests. They are opportunistic predators, expanding their range, altering food webs, and embodying the very definition of "invasive" under U.S. law.

Florida's classification is not cosmetic—it reflects ecological risk. To call them "non‑native but not invasive" is to ignore both the legal framework and the documented spread of populations. The myth dissolves under scrutiny: veiled chameleons are invasive, and their management is a matter of ecological stewardship, not semantics.