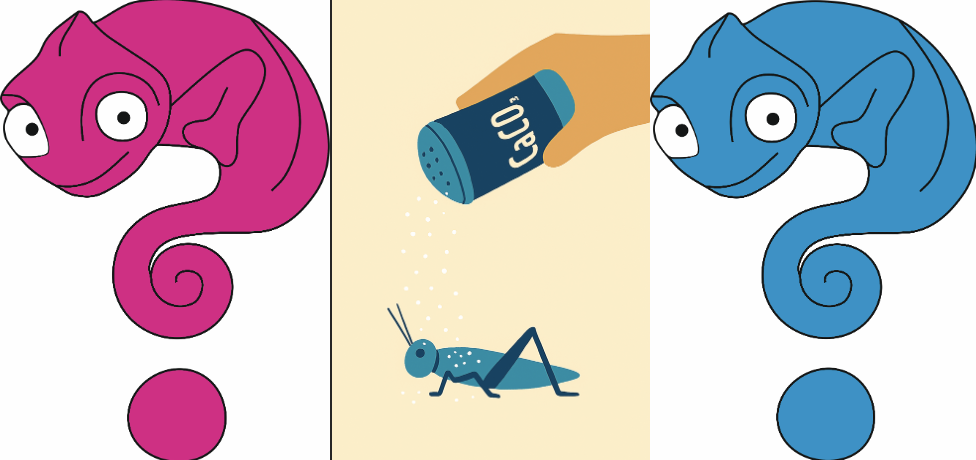

Myth 4: “Light Sprinkling with Calcium Powder"

Why Minimalism Kills, and Rich Dusting Saves Lives

In recent years, a trend emerged among keepers: the so-called "light sprinkling" of calcium powder on feeder insects. This advice is not just misleading—it's biologically incoherent and lethally insufficient. Let's dismantle it.

The Role of Calcium in Chameleon Physiology

Calcium is a critical mineral for all vertebrates, including chameleons. It enables muscle contraction, nerve transmission, blood clotting, and—most visibly—bone formation and egg production. Without adequate calcium, metabolic collapse is inevitable. In growing juveniles and gravid females, calcium demand spikes dramatically. Deficiency leads to metabolic bone disease (MBD), paralysis, and death.

What "Calcium Powder" Actually Is

The term "calcium" is a linguistic shortcut. What's sold as calcium powder is typically calcium carbonate (CaCO₃)—a compound derived from geological and biological sources:

Limestone deposits (sedimentary rock)

Crushed eggshells (avian origin)

Seashells and coral fragments (marine origin, often aragonite)

These sources differ in bioavailability and purity. The term "calcium" obscures this diversity. In reality, keepers are dusting with pulverized geology—often aragonite or calcite—whose absorption depends on particle size, gut pH, and vitamin D₃ status.

Calcium Metabolism in Chameleons

Once ingested, calcium is absorbed in the gut (vitamin D₃-dependent), circulated via blood, and deposited in bones or eggs. In females, calcium is mobilized from skeletal reserves to form eggshells—a process that, if unsupported, leads to catastrophic depletion. Excess calcium is excreted via feces. Importantly, chameleons do not form internal calcium deposits—no renal calcification, no soft tissue ossification. Their physiology is adapted to episodic surges of calcium intake.

Natural Calcium Exposure in the Wild

In native habitats—Madagascar, Africa, Arabia—chameleons encounter calcium-rich dust daily. They ingest it inadvertently while feeding on ddust-coated insects or licking particulate matter from foliage with dew droplets. These dusts originate from CaCO₃-rich soils and coastal plains, often windblown and abundant. High-dose calcium exposure is not an anomaly—it's ecological baseline.

The Calcium-to-Phosphorus Ratio

The ideal Ca:P ratio in feeder insects should exceed 2:1. Most feeder insects (crickets, roaches, worms) have inverted ratios—high phosphorus, low calcium. Without correction, phosphorus binds available calcium, forming insoluble salts and triggering renal failure. This imbalance is a silent killer. The kidneys lose function, urates become gritty, and death follows.

The Fatal Flaw of "Light Sprinkling"

"Light sprinkling" fails for two reasons:

Mechanical loss: Powder falls off feeders before ingestion.

Biochemical insufficiency: Even if ingested, the dose may not counteract phosphorus load.

When calcium is too low, phosphorus wins the biochemical war. The kidneys suffer. The bones soften. The animal dies.

The Correct Protocol: Rich, Visible Dusting

There is no known risk of calcium overdose in chameleons. Excess is excreted harmlessly. Therefore, generous, visible dusting—not minimalism—is the correct strategy. Powder should coat feeders like snow. If it looks "too much," it's probably just enough.