The Chameleon That Shouldn’t Be There

A newly confirmed population of African chameleons (Chamaeleo africanus) in northwestern Peloponnese adds complexity to Greece's conservation landscape. Found near Kalogria Beach in the protected Lamia and Strofylia Forest zone, these chameleons match genetically with populations from Egypt's Nile Delta, proving they are not indigenous but introduced. While some speculate the introduction occurred in antiquity, there is no evidence — not a single indication — to support this. On the contrary, Peloponnese has been subject to decades of intense herpetological research, and no historical records suggest ancient presence.

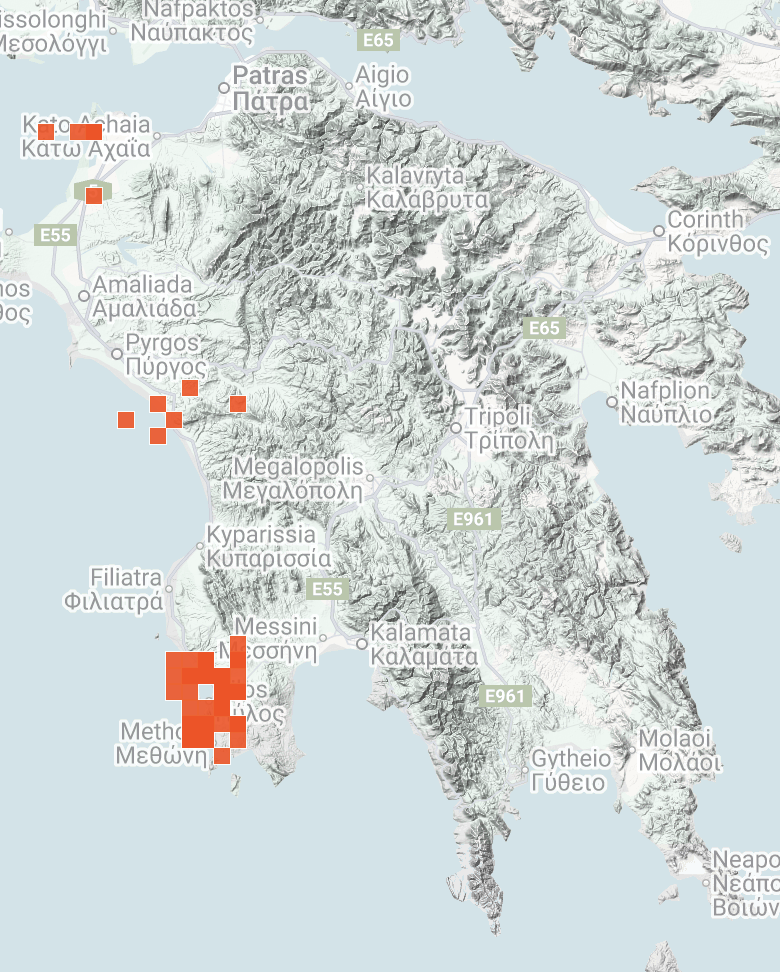

Originally, C. africanus was discovered only in the Gialova Lagoon near Pylos. Over the years, new populations have appeared progressively farther north, culminating in this latest sighting. This pattern suggests active spread, possibly due to a more recent introduction — or even climate-driven expansion as warming trends reshape Mediterranean habitats.

Despite being non-native, the species is paradoxically protected under Greek law rather than treated as invasive. This legal status raises questions about conservation priorities: should a proven non-indigenous species be shielded from control measures? So far, its ecological impact appears minimal, but no formal studies have confirmed this.

The discovery of newborn individuals in the new population suggests a self-sustaining group, prompting calls for further research into its demographics, habitat use, and potential interactions with native fauna. Whether this expansion is a result of human introduction, natural dispersal, or climate change, the presence of C. africanus in Greece challenges conventional definitions of "native" and "invasive."

As conservationists weigh the implications, one thing is clear: the African chameleon's quiet spread across the Peloponnese is no longer anecdotal — it's a biological reality, and one that demands thoughtful ecological and legal attention.